Visit the Lab Pushing Nobel Work to the Next Level

From original article in Ohio State Alumni Magazine by Jenny Applegate, with Photos by Jodi Miller.

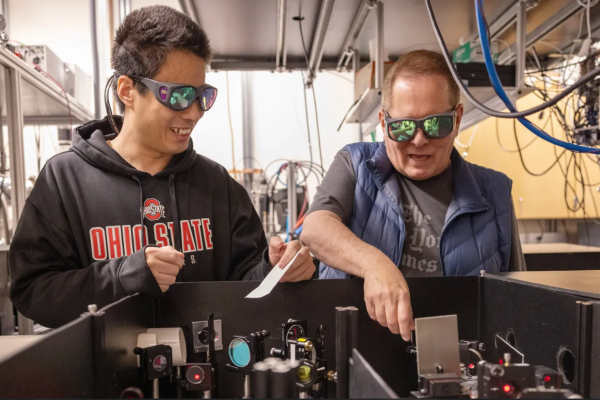

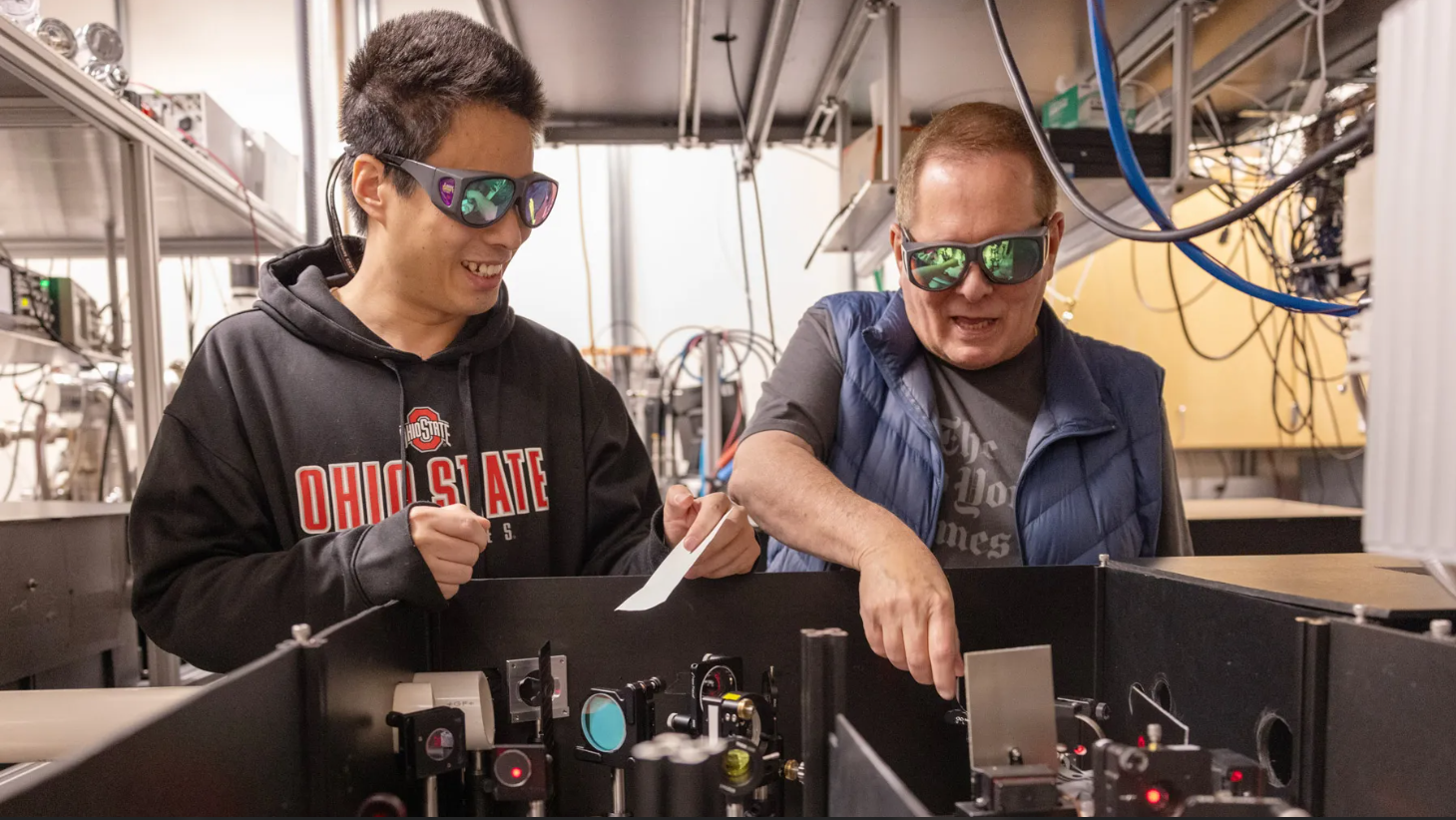

Professor Lou DiMauro has a New York accent and eyes that crinkle the same whether he’s cracking a joke or explaining complicated physics. Both skills come in handy when your lab partner wins the Nobel Prize.

Together, DiMauro and Pierre Agostini run the Ultra-fast Atomic Physics Research Group named for them. In fact, as Ohio State recruited DiMauro from the prestigious Brookhaven National Labs in 2003, he told leaders to consider Agostini, too.

“Even back then, I believed he could win a Nobel,” DiMauro says.

That’s because Agostini’s work helped establish a way to track electrons as they zip around at 1,400 miles per second inside atoms. Electrons are one of the building blocks of atoms; in turn, atoms are the building blocks that make up everything — from your body, to your coffee and the cup it’s in, to stars in space.

Observing things moving so fast requires, essentially, super-short shutter speeds, so Agostini explored light pulses that can be measured in attoseconds. To put a point on how incredible and mind-boggling that is, there are as many attoseconds in one second as there have been seconds since the universe began.

“It’s our elevator speech that what we’re doing is making molecular movies,” DiMauro says.

The son of Sicilian immigrants (his father is a jazz drummer who played with the legendary Charles Mingus), DiMauro grew up in New York, married a New York girl (Barbara DiMauro) and together raised their kids (filmmaker Dan DiMauro and neurologist Kimberly DiMauro ’12) there, too. Three opportunities lured him to Columbus and his post as the Edward and Sylvia Hagenlocker Chair/Professor of Physics: building his own group, working with students and having more freedom and resources to pursue the science that fascinates him.

“The public thinks of physicists as Albert Einstein and theorists who sit at their desk with paper. But one of the great founders said it best: Physics is really an experimental science,” he says. “It’s the experiment that drives new thought.”

At its most basic, a chunk of what the Agostini-DiMauro group does is shoot lasers into vacuum tubes to reveal how energy and matter work. Physicists call the process harmonics, and the lasers provide the attosecond light pulses. The goal is pure knowledge.

“I think I also speak for Pierre when I say we’re less interested in the applications, although the applications are important,” DiMauro says. The Department of Energy, National Science Foundation and Air Force agree. They’re some of the group’s biggest funders.

Just as Agostini’s Nobel-winning work enabled the research being done at Ohio State and around the world today, DiMauro wants his team’s work to empower the future.

“The quantum computer is a perfect example,” he says. “Things that we now understand very well — quantum mechanics — people are taking those fundamental physics and turning it into a machine that looks like your desktop computer but holds far more power and promise.”

One Friday last month, DiMauro opened the doors of his home and lab to us.

8 a.m. I have coffee and half a bagel and play The New York Times’ mini crossword puzzle and Wordle. Then I start work. I’m not teaching classes this semester, which worked out well considering Pierre’s Nobel, but I’m so busy it’s hard to find time to drive to campus.

9 a.m. I join a Zoom call with Pierre, who’s in Paris most of the year, and Jessi Middleton ’11, our office administrator. We discuss who Pierre will invite to Nobel events in Stockholm, where Ohio State is planning a celebration. It’s important for the university to be there because this audience should know us.

10 a.m. I pause work to feed our Italian greyhound, Pepper.

11:15 a.m. I drive to campus and arrive at the Physics Research Building. In my office, I get ready for Journal Club, when my group and Pierre meet with Associate Professor Alexandra “Sasha” Landsman’s Ultrafast Laser-Matter Interactions Group to talk about research, the latest in our field and our own. Our groups are interested in similar things, but she focuses more on the theory side.

11:30 a.m. Pierre joins on Zoom as we’re working out some problems with the conference room audio. ”This is what 18 physicists do all day,” I tell him, which gets a laugh from the students.

11:45 a.m. Postdoc Abdallah AlShafey ’22 MS, ’23 PhD, from Sasha’s team, summarizes a paper he researched about harmonics in crystals. There’s high interest in this right now. He references another paper, done here in 2011, that’s gotten lots of citations. That’s what we want. It’s no fun if our colleagues and competitors don’t take notice.

Noon Postdoc Sha Li, who goes by Lisa, is the person on my team experimenting in this. She asks good questions and shares what she’s observed.

12:15 p.m. We work through lunch — my usual. Back at Brookhaven, I played basketball on my break and fell out of the habit of eating.

12:25 p.m. Grad student Eric Moore, from my team, presents next. While Lisa works in solids, Eric and postdoc Tahereh Alavi are experimenting in liquid, the least explored state of matter. That’s because it’s disordered: If you think about how the liquid sloshes when you shake your water bottle, that means the atoms are constantly reconfiguring, too.

12:55 p.m. Eric and Tahereh are seeing electrons behave in unexpected ways, so the group raises questions and tosses out ideas about why that might be. It’s valuable. If our research is thoroughly challenged and thought out, it stands up better when published.

1:10 p.m. Today is the birthday of PhD student Dan Tuthill ’19 so we all meet for donuts in my students’ office. We discuss candy in different countries — we’re a diverse bunch with people from China, Mexico, Iran as well as the U.S. And then, I don’t know why, we get to talking about Taco Bell.

1:30 p.m. I return to my office and check my and Pierre’s email inboxes in case any need urgent responses. It’s a light day in our lab, and I go visit students next. They’re the reason I’m still doing this at 70.

From original article in Ohio State Alumni Magazine by Jenny Applegate, with Photos by Jodi Miller.