5 for pride: These Buckeyes have a Nobel history, too

From original article for Ohio State Alumni Magazine by Jenny Applegate

Pierre Agostini is the first sitting Ohio State professor to be named a Nobel Prize winner, and these professors and alumni also were honored.

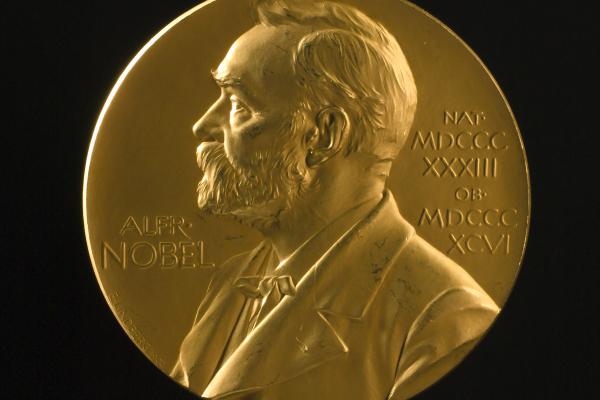

This is the replica of his Nobel Prize medal that Pierre Agostini presented to Ohio State. (Photo by Jodi Miller)

Professor Emeritus Pierre Agostini may live in France most of the year, but he is a regular presence for Ohio State students in the Agostini-DiMauro Atomic Physics Research Group, spending at least one lunchtime a week glued to his Zoom screen so he can help coach them through understanding and developing new research.

He was, let’s say, less accessible when the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences tried to reach him to let him know he had won the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physics. He found out from his daughter, who saw the news on Google and called to ask if it was true.

Agostini, who joined Ohio State’s faculty in 2005, was honored alongside Ferenc Krausz and Anne L’Huillier for his 2001 work that helps physicists track the movement of electrons within atoms. It was foundational knowledge, says Peter Mohler, executive vice president of Ohio State’s Enterprise for Research, Innovation and Knowledge and chief scientific officer of Wexner Medical Center.

“There is inherent value in having foundational knowledge in our fields,” Mohler says. “It forms the basis of curiosity and ideas that others will take to create the next level of foundational knowledge.”

Here are four more Nobel-honored Buckeyes whose work has led to big advances.